Pricing rules in Japan; an awkward development

June 8, 2018

Tosh Nagate, CEO at e-Projection K.K.

To make assumptions of the price of any product, from chocolate bars to computers, is one of the most daunting tasks for a product manager, but if it comes to drug pricing, the challenge is staggering. In many of the advanced economies, unlike any other product, drug prices are ultimately determined by the authorities, and drug makers are “price takers,” although in many cases the supplier still can negotiate. The question those companies will have to ask to themselves will be, how can we convince the authorities to make believe that our new drug is worthwhile this price that we think?

Cost Calc: Only in Japan

Japan is probably the only country in the world that has a mechanism to price drugs based on its manufacturing cost. It is called the “Genka-Keisan Houshiki,” or the Cost Calculation Method, which basically stacks up the estimated cost per unit, and adding some margin on top of it, BOOM! Here’s the price. The Japanese authorities, when they receive an application of a new drug to be listed in the National Health Insurance list, or the NHI list, they first look inside the market whether there is some drug that is already approved and has a price tag on it. If there is, then they don’t need to worry that much, they can just benchmark on that Comparator drug. But if they couldn’t find any, the story gets complicated. They ask the applicant to hand in all the documents that will support the estimation of the cost structure of the product. The applicant needs to collaborate with the authorities to clarify the evidence that supports every cost component of the product. Here are some of the factors that the Chuikyo, or the pricing authorities in Japan, just announced in May 16 that they said that they will use when calculating the price of the drug.

Standard factors for the Cost Calculation Method (source: Chuikyo document on May 16, 2018)

| 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Hourly labor cost | JPY 3,818 | JPY 3,645 |

| SG&A (%) | 45.2% | 46.9% |

| Operating margin (%) | 14.7% | 14.3% |

| Distribution expenses (%) | 7.3% | 7.4% |

| VAT (%) | 8% | 8% |

This needs some explanation. Essentially what they are saying is that since the actual cost structure of the new drug is yet to be known, these numbers will be used as assumptions when they try to estimate the actual cost component when the drug hits the market. They will allow you to calculate the labor cost at JPY 3,645 per person per hour in order for you to calculate the entire cost structure of your product. They are even saying that they will generously allow you to collect 14.3% of an operating margin from your product. Congratulations!

Of course, things are not that easy. What can go into the Cost of Goods Sold is still unclear. How are we going to count on depreciation of fixed assets shared by more than one product? Can we double count it, or do we have to divide it by the number of products that are sharing that same asset? How about the economies of scale? Can we accurately predict the CoGS of a product when it reaches to scale, only based on what we know now? If you have some experience working with the finance department, you know that measuring the cost structure of a marketed product is already a tough job. Predicting that before the rubber meets the road is far from easy.

Bottom line: No blames on me

Why do the Japanese authorities, despite the technical difficulty of applying the method, try to keep using the Cost Calc? The formal reason is to ensure stable supply of any drug that is approved and reimbursed, and they are trying to avoid outage of drugs because of financial reasons at the supplier side. Therefore, they are allowing the manufacturers to come up with the estimated cost and even make some money out of it for the suppliers to not to go out of the business.

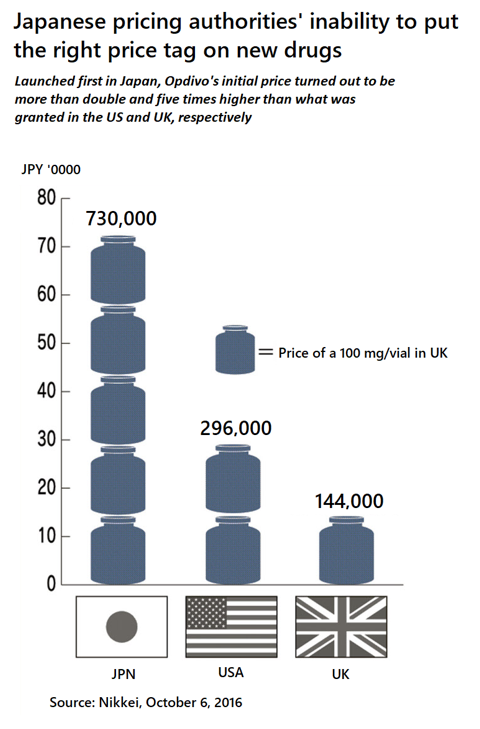

But the true reason behind this is the inability of the authorities to study the true value of any drug by themselves. It is easy to do so when there are comparables which already has a price tag on it. But for an entirely new drug, they do not have the capabilities to assess the clinical, intrinsic value of the product, and therefore they need someone to tell them what that is. One good example was Opdivo. This product was first launched in Japan in 2014, by a Japanese company called Ono Pharmaceutical. The authorities were so excited that it was Japan, not any other country in the world, that brought this innovative product first to the market, they made a mistake on it, in the wrong direction. The NHI price of Opdivo was so high that this issue climbed all the way up to the Diet in 2016. The consequence of this came couple of years later, when the price of Opdivo was cut to an unprecedented degree. Since then even more so, the pricing authorities excuse was that it was not themselves that came up with the numbers, but it was the company. “Don’t blame on me.”

Turning illiteracy into opportunity

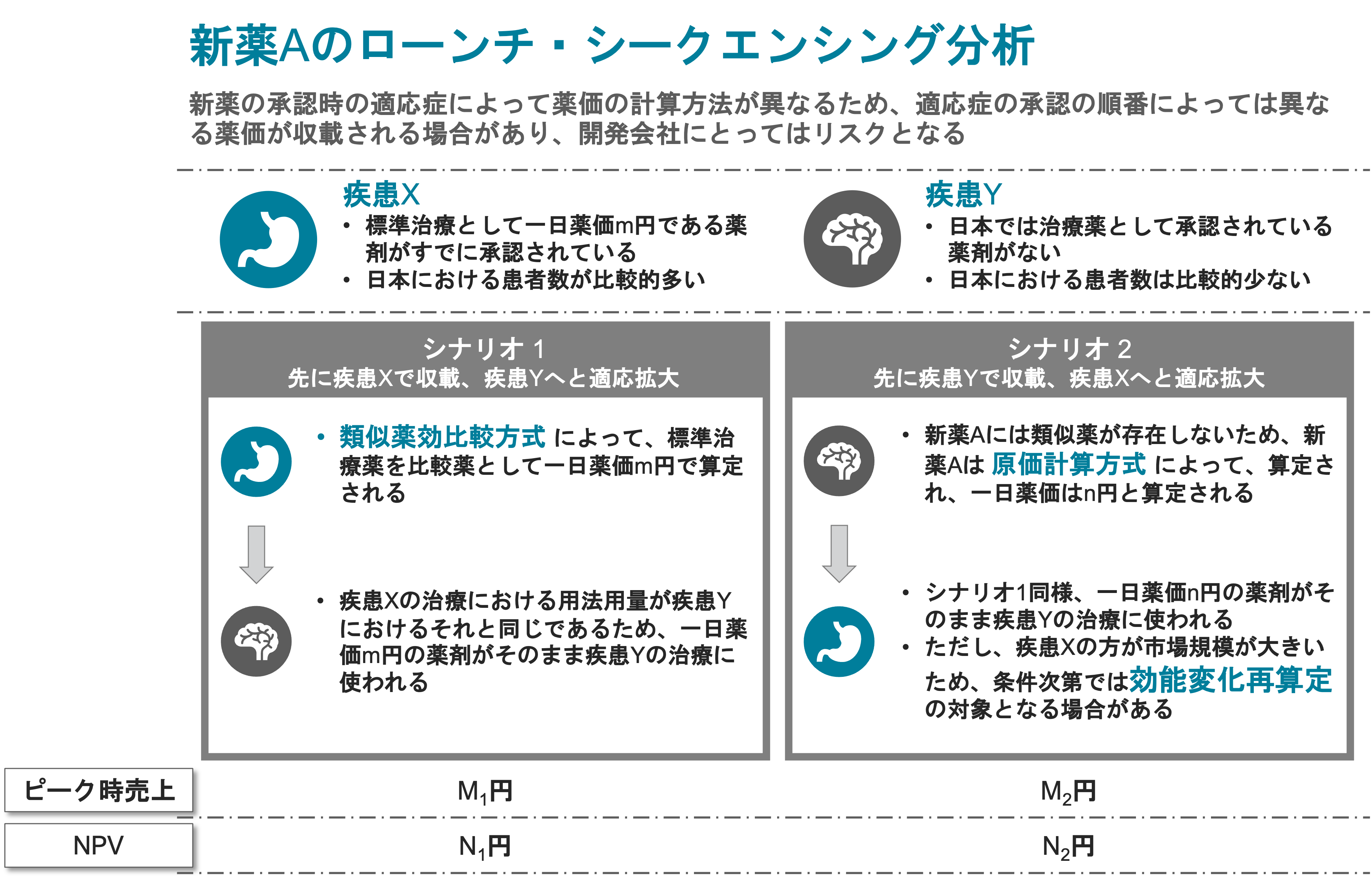

This rather naïve attitude is somehow seen all over the place across the Japanese authorities. However, from a pharma industry perspective, this is somehow providing freedom to negotiate with the price regulators. There are a handful of strategic initiatives for the industry to put pressure onto them to receive a nod on the prices which they propose.

- European prices: it is very well known that the authorities are strongly mentally bound to prices in major European countries if the product is already available there with a tag on it, even if by this Cost Calc method. This makes sense if you think about the discussions that we already had; the authorities need an excuse. American prices are usually not applicable to this, but still there will be some benchmarking around this even if the product is only launched in the US, such as 50~70% of the US price.

- Launch sequencing: everybody who knows global pricing and market access of drugs also knows that in the UK, for the first year of your new product launch you can put whatever price tag you want to on it. So, ask for a high UK price, and then apply for the NHI pricing list in Japan. Don’t worry. The pricing authorities in Japan are obligated to list the price within 3 months maximum, and they cannot negotiate further unless you withdraw the application. You might think that maybe they already know this mechanism so that this might not work, but once again put your feet in their shoes. They are looking for excuses, not rationale.

On the other hand, if you are not so confident in your prices in Europe or because of other reasons not comfortable in putting an extreme number in UK, the other strategy is to launch in Japan first to induce the “miss-pricing” in your favor e.g. the case of Opdivo. Although there could be potential ripple effects if you cannot negotiate a high price with the Japanese, but in that case, you can simply withdraw the application and then wait for the European prices to come. Japan is only 7% of the global market, so the stakes are not so big, but if you can get to double your price in Japan that’s a different story. This bet might be worthwhile. - Japanese licensee: any government in the world will favor domestic companies over their foreign counterparts. Japan is not an exception. But as you see in the case of Opdivo, chances are that there is a high probability of getting the “miss-” or “gratuity pricing” when it is a Japanese company that is applying. So, planning to come to Japan even in early phases of development by licensing the product, is a reasonable strategy.

Knowing who you are going to be talking to is one of the most important success factors in any situation. Once you know the market, Japan will turn to represent a great opportunity for your innovation.